It's in the head 1

Topical diagnosis

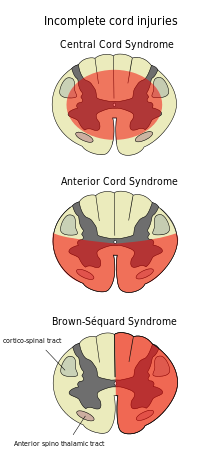

I'm currently working in neurology, where I've previously worked as a psychiatric consultant. Here, patients with neurological diseases such as multiple sclerosis, brain tumors, Parkinson's disease, and ALS are treated. Being a university hospital, it's the last resort for many diseases where advanced treatments are offered, such as for Parkinson's disease, but it also receives patients with mysterious symptoms. Patients often undergo multiple examinations including brain imaging with MRI, lumbar puncture for various markers in cerebrospinal fluid, and electrophysiological measurements. The core of classical neurology is what's called topical diagnosis, where conclusions about the location of a suspected lesion in the nervous system are drawn through a thorough clinical examination. This can then be confirmed or ruled out, for example, with MRI. This way, one can see that the symptoms are linked to the underlying disease process. A typical example is a spinal cord injury that affects the function of the extremities in different ways depending on its location. Let's say there's an injury to the spinal cord primarily on one side, perhaps due to a penetrating injury from a knife or bullet. This results in ipsilateral (same side as the injury) loss of motor function, proprioception, and sensation for vibration and touch. However, the contralateral side (opposite to the injury) is affected by loss of sensation for pain and temperature. This condition, known as Brown-Séquard syndrome, occurs because the nerve pathways for pain and temperature (lateral spinothalamic tract) cross the spinal cord at each segmental level, while the pathways for touch cross first in the medulla oblongata (the elongated spinal cord).

Functional symptoms

It's not uncommon for patients to seek help with complaints that don't add up. Often, they are diffuse, affect sensation, move around, and vary in intensity over time. If imaging studies or similar tests are conducted, no pathology is found. In such cases, we talk about functional neurological symptoms (FNS). These are various conditions where it's the function of the nervous system that is faulty rather than its structure. Some liken this to distinguishing between software and hardware to describe how a computer functions. However, this is a simplification, as it could be a matter of how diligently one searches for organic changes, and also because our mental well-being affects symptoms even in clearly neurological diseases. Take epilepsy, for example. It's a condition where the brain experiences synchronized activity during seizures that can cause the patient to lose consciousness and have tonic-clonic seizures. This has a typical appearance and can be treated with medication. However, there are also functional seizures, where patients experience atypical symptoms during seizures. Even if the electrical activity is measured with EEG (electroencephalography), the typical epileptic activity is not observed. The problem, however, is that it's not always easy to determine the nature of the condition, and even patients who actually have genuine epilepsy can experience functional seizures.

Functional symptoms usually don't stem from patients making things up! Sometimes there are secondary gains where a patient may simulate symptoms, but most often it's genuine distress. Furthermore, there's a gender issue where women are more frequently doubted than men (here's a compilation). For example, multiple sclerosis often causes diffuse symptoms that couldn't be diagnosed in the past because imaging methods weren't as advanced, and inflammatory activity in cerebrospinal fluid couldn't be measured. Consequently, people's suffering was sometimes questioned, and no treatment was provided (on the other hand, there often wasn't any effective treatment available).

Hysteria

The word "hysteria" originates from the Greek word "hystera," meaning uterus. It was a condition in women that has been used throughout history to describe women who didn't behave according to the norm and was a mix of various conditions. It could range from psychiatric conditions like personality disorders to epilepsy, multiple sclerosis, or FNS. In Egypt and ancient Greece, it was believed that the condition originated in the uterus, while in the 18th and 19th centuries, more psychological explanations were discussed. Here, the French neurologist Jean-Martin Charcot is worth mentioning, as he, during the 19th century at Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, presented patients with hysteria and demonstrated how he treated them with hypnosis.

The term hysteria soon fell into disrepute as it was rightly considered misogynistic and too broad. Sigmund Freud published a book in 1896 attempting to describe the origin of hysteria and presented the thesis that it was due to sexual abuse during childhood that women had been subjected to. However, he argued that men could also suffer from hysteria. The solution to the problem was psychotherapy with hypnosis, where previous traumatic experiences or fantasies would be uncovered and addressed.

Treatment of FNS

Jon Stone is a professor of neurology in Edinburgh and has devoted much of his career to understanding FNS and educating colleagues and the public about it. Here is a website for the public. Nowadays, it's believed that FNS can be precisely diagnosed, thus reducing the risk of unnecessary extensive investigations and instead providing appropriate treatment. The requirement for an identifiable psychological stress factor believed to trigger the symptoms has also been abandoned.

The first step is to identify the condition. For this, there are several neurological findings described, including in this review article. For example, when examining a paretic (weak) arm, such as after a stroke with Grasset's test (arms stretched upward), one might find both a lowering tendency and pronation (inward rotation of the hand). In FNS, one often finds only lowering. Another example is distracting the patient with exercises that require attention (counting backwards from 100 in steps of 7) and thereby observing a change in symptoms. This way, you "trick" the patient by redirecting their attention elsewhere and not focusing on the symptom in question.

When clinicians have determined that it's a case of functional symptoms, they inform the patient as clearly as possible. This involves psychoeducation where they must convey reassurance in the diagnosis and the good prognosis. It's important to be satisfied with the investigation already conducted and not go further just to "be on the safe side." Otherwise, there's a risk that the uncertainty will spread to the patient, leading them to seek care from other providers unaware of the investigation already carried out.

The third step involves various forms of psychological treatments, such as CBT, aimed at challenging thought models that something is wrong with the body and also at exposure therapy. For more motor symptoms, physiotherapy or occupational therapy may be helpful. If there's a suspected psychological stress factor, more targeted therapy for this may be appropriate.

Conclusion

Just because something is "in your head" doesn't mean it's not real. The patient's experience is by definition subjective, and suffering cannot be ignored just because a clear cause isn't found. Here, I've focused on neurological symptoms, but the same approach can also be used for other organs. It could involve chronic pain conditions or functional gastrointestinal disorders or, for that matter, post-infectious conditions like post-COVID. The important thing is to provide reassurance and also to reasonably exclude organic causes. Unfortunately, there's still ignorance not only within healthcare but also among patients and their families about functional disorders. Some feel offended and mistrusted, while doctors in some cases neglect the patient's symptoms.

In upcoming posts, I'll write more about how functional symptoms can affect groups of people in the form of mass hysteria.

Excellent article - I hope to write something similar soon, it’s an interesting topic